School FAQs

These are FAQs about high school and college.

S-1. Why did you transfer from Harvard to MIT?#

Short answer: mostly social reasons, I’m too nerdy for Harvard.

Long answer: See here.

S-2. I’m interested in learning some higher math. Where can I start?#

If you like my writing and are comfortable with proofs, try my Napkin. It was basically written to answer this question. Other possible references are mentioned in Recommendations.

See also S-6 below.

S-3. How do you live-TeX your notes so quickly?#

See FAQ L-14.

S-4. How did you take undergraduate / graduate math classes in high school?#

Context: in high school I took five classes from UC Berkeley and San Jose State total; you can see the notes I took.

The main limiting factor is getting your high school to let you run off. Every college professor I’ve met is more than happy to help out a high school student who is interested in learning more math. (This may be untrue at certain top schools just because those professors get more audit requests than they can actually accommodate.) It’s the high school bureaucrats that put their foot down.

Talk with your high school administration and see if you can strike a deal. If one person says no, talk to someone else. You have to be aggressive with these things to make progress, because otherwise the administration has no real incentive to help you.

S-5. What are your thoughts on high school math research?#

I’m pretty cynical of it. The (buzz)word “research” itself is a red flag for me: it sounds like the kind of thing people want to say they’ve done, rather than want to do.

I won’t say it’s always a bad idea, but I think you should really ask yourself what you are hoping to get out of it. You should definitely not attempt math research because you see other people doing so.

On the topic of research, some excerpts from Euler Circle which I agree with:

You may be familiar with high-school “research” in biology, where a high-school student works in a lab over a summer, mostly doing menial tasks like cleaning test tubes, and is rewarded with a paper to publish or to present in science fair competitions. . . . There is no mathematical equivalent of cleaning test tubes.

You simply cannot expect to work for a few months over the summer and have something to show for it. An exceptional high-school student should expect to spend around 1000 hours over the course of two years on research in order to have a reasonable (but far from certain) chance of producing a publishable paper.

Nonetheless, there are good research-based programs out there. Consider programs like PRIMES and Euler Circle itself.1

With that said, if a high school student is interested in higher math, my personal recommendation is to also learn new subjects. (See S-2 and S-6 for hints on how to do this; it’s possible to do this alongside good research projects too.) Reason: there is way, way too much math to learn beyond the calculus / linalg / multivar.

I put it this way: look at the Napkin topics diagram. All of this material is stuff that a strong undergraduate is likely to learn over their four years of university, and more. (It does not include most graduate-level topics.) Each of these nodes has at least as much theory as olympiad Euclidean geometry (and in many cases the comparison is off by an order of magnitude). Personally, I think it doesn’t make sense to pursue research until you have at least completed abstract/linear algebra and real/complex analysis at the absolute bare minimum. (And really you want more than that.)

Patiently learning foundational material is admittedly neither flashy nor attractive. (There’s no equivalent of Regeneron STS nor does it help much with your college apps.) But I think long-term it is more useful to study fundamentals than rushing to collect honors.

S-6. I want to take some advanced math classes from nearby college, which ones do you recommend?#

Short answer: If you can read and write proofs, then

- Learn abstract algebra or real/complex analysis; and

- Avoid linear algebra or multivariable calculus.

(If you aren’t comfortable with proofs, you should learn that first. See C-5 for advice on that.)

Long answer:

I am assuming you are interested in learning a lot of math eventually (rather than, say, learning math for the sake of physics / engineering / etc., which is fine, but then this advice is not for you). In that case, I think both linear algebra (as it is usually taught) and multivariable calculus are significantly overrated for people who (a) know how proofs work, and (b) want to pursue higher math.

Linear algebra is useful, but when taught as a standalone class, you will mostly be doing manipulations with matrices. It’s not a bad thing, but I think it’s not something that needs to take one whole semester if you’re going to eventually redo the whole thing abstractly with $k$-modules anyway. I would rather spend the semester learning abstract algebra as a whole (which includes the abstract treatment of vector spaces), which is the language required to do anything algebraic. Many higher level courses are going to assume you know what a domain is, an ideal is, etc. and you would like to learn this as soon as possible.

Multivariable calculus and ordinary/partial differential equations is a bit of a dead end, in my opinion, unless you are interested in these topics for their own sake (in which case you should just learn them, not let random strangers on the Internet tell you what to do). Real and complex analysis, together with enough point-set/metric topology to go with them, are more valuable as core material: many higher level courses are going to assume you know what a compact set is, a real manifold is, etc. and you would like to learn this as soon as possible.

I think the reason that linalg/multivar are so popular is that you don’t need to understand proofs to take these classes, so they appeal to a broad audience. But if you do understand how to read and write proofs, you are quite lucky, and you have some better options available to you for where to explore next.

S-7. How do I get in to MIT?#

You are asking the wrong person; I am not an admissions officer. Instead, you should read mitadmissions.org. For example the post Applying Sideways will literally tell you the answer to this question2, even though it’s not the answer you want to hear.

I have nothing to add to this. Really.

People always want to believe there are some mythical criteria or hidden goals in the admissions process, a closely guarded secret held from the public, and hence the best route is to find out this insider information. No, seriously, just listen to the people who do admissions for a living.3 MIT is not the Illuminati, even if it is a subsequence.

S-8. Is it worth looking at olympiad problems in college if I didn’t do competitions in high school, or should I just stick to college math classes?#

The short answer is that it depends on what you want.

The model you can have in your head is something like follows:

- High school olympiad problems are designed to train for problem-solving and thinking ability. To this end, they often take pride in not requiring much background outside geometry (and even then not much).

- College math classes, and the associated homework, is instead focused mainly on learning the relevant material. The exercises for your abstract algebra class are geared towards, well, helping you learn abstract algebra. The problem-solving component plays a less important role (though different professors might emphasize it more).

Both options will contribute at least to mathematical maturity. I privately think the math contest syllabus does a better job of developing mathematical maturity and proof-writing at least in beginners, but that’s something I consider my own opinion.

That means, depending on what you want, there are a lot of possible answers. Here’s a few.

- If you are just thinking to major in math, and are worried that you are “missing out” or “behind” by not having done contests, then my advice would not be worry about it. The biggest hurdle will be getting acquainted with proof-writing, which is a challenge, but one that everyone goes through.4 I wouldn’t go as far to say that it’s not worth it, just that (1) having immense problem-solving ability is not that important, (2) you’ll get mathematical maturity from the standard curriculum anyway over time, and (3) fear-of-missing-out is not a productive form of motivation anyway.

- If you are thinking about pursuing math as a career, then it’s a bit more of a toss-up. Both problem-solving ability and familiarity with core material are useful powers, and their importance even varies depending on which specific field of math you are looking to do.

- If you’re just curious what math contests are all about or doing this just-for-fun, then by all means go exploring! Pursuing your interests is important. I really mean it when I say that olympiad problems are works of art. If you want a chance to appreciate some really well-designed challenges, come on through, we’ve got a show for you. (Well, not that higher math isn’t beautiful too.)

And so on. In short, it depends on what you’re hoping to get out of your time. The example scenarios above are totally black-and-white, but your situation is likely to be more complicated, say, a mix between these.

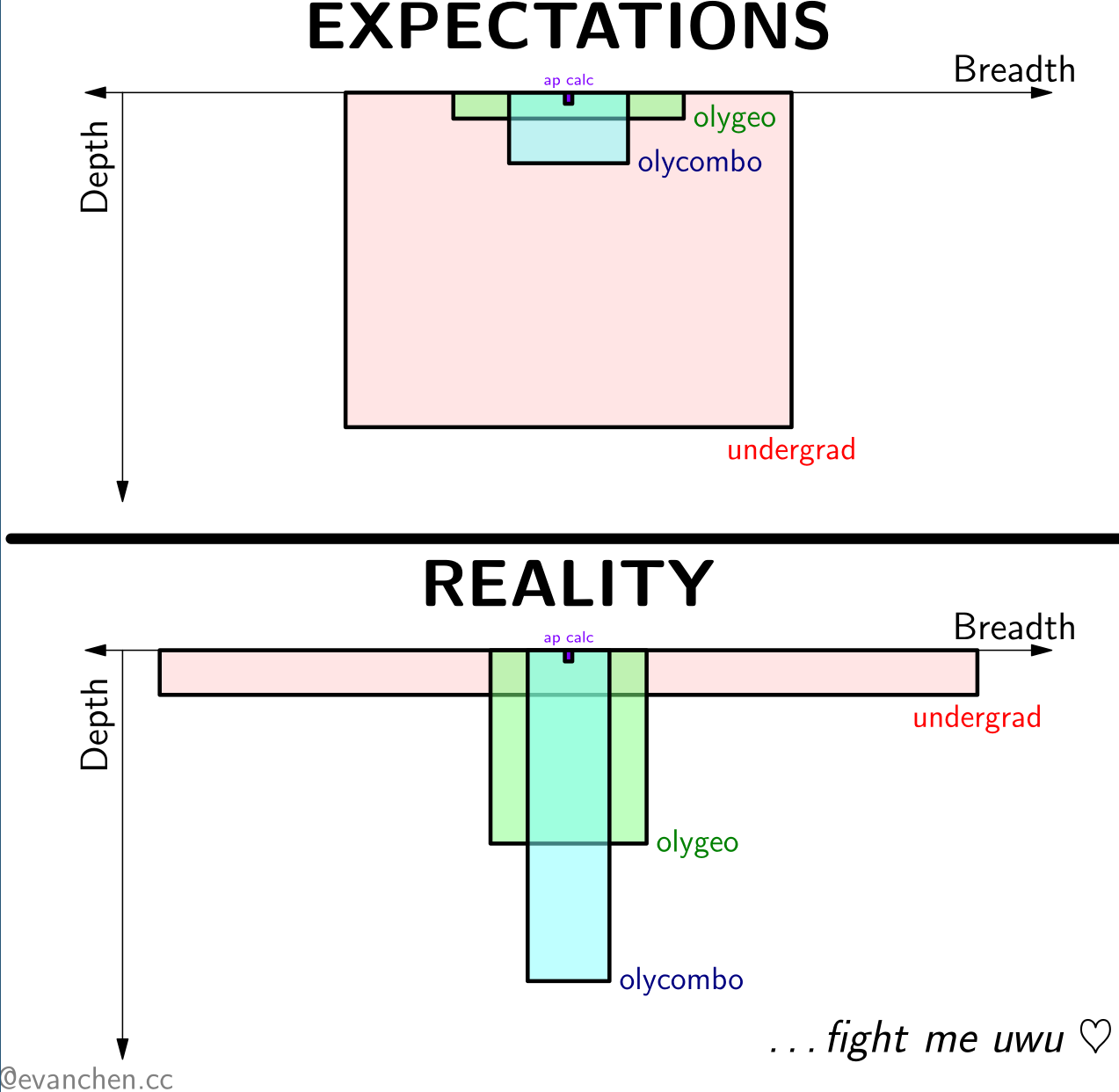

S-9. What’s the difference between high school contest math and undergraduate math?#

From my Instagram:

S-10. What’s the distinction between calculus and real analysis?#

It’s an Anglo-Saxon distinction; in many parts of the world, there is no such thing as “calculus”.

But to answer the question, calculus can be thought of as real analysis with proofs, definitions, and coherent theorem statements deleted. The link above gives some more details.

If you’re a proof-capable math student asking this question because you don’t know which textbook to read, I would generally recommend the texts labeled “analysis”. The books labeled “calculus” have a different target audience. You should not feel obligated to “learn calculus first”. (Napkin takes this approach, where the tongue-in-cheek “calculus 101” part has metric topology as a prerequisite.)

For book recommendations, I grew up on Pugh’s Real Mathematical Analysis which I liked, but have heard second-hand recommendations for Tao’s Analysis I as well. The most famous book is Baby Rudin, but I have heard mixed things about it.

S-11. What’s undergrad life like in college?#

I think this will vary wildly from person to person and depend a lot on certain subfactors like

- what living group you’re in;

- what activities you do;

- and what courses you take, because unlike high school, you have so many courses to choose from and so much more choice what to take.

The relative importance will vary by which school you go to. When I went to MIT the order for me was clearly dorm > activities > classes, because MIT has significant living group and dorm culture, and student activities are one of MIT’s distinctions. As another example, in schools where dorms are assigned randomly the choice of dorm you end up in will tend to be less important because the dorms are all (because of the randomness) similar overall, although your luck with roommates may have an effect.

S-12. I’m a high schooler trying to decide on prospective majors and careers later on. Do you have advice?#

In general, trying to optimize for college majors is premature5 until you actually know which university you’re attending (because you want to know what the department there is like, what the requirements are, etc.). Career advice is even more premature.

With that disclaimer, a lot of you still want to hear me yap about math majors, so here are some hints about math majoring that may or may not be useful to you. (They will necessarily be limited in value because they are broad strokes about general trends at a few universities that may not apply to the college you end up actually attending.)

- Many university math exams do not require the level of problem-solving demanded by contests like the USAMO/IMO. (I think people tend to overestimate the average amount of problem-solving required because they see that olympiads are branded as a high-school contest and assume college is even scarier.)

- Many university math major requirements are quite lax. For example, at MIT you can get a math major only taking 1 math class per semester. So I often encourage otters at MIT to still at least consider math majors, even if they don’t want to primarily study math and they have zero interest in going into academia, because in some cases they’d nearly get the major by accident while taking the math classes that sound cool.

- Broadly, in the United States, your choice of major matters much less for career options than many people believe. (Like, my brother was an English major, and then later switched into a job in software programming.)

S-13. Any advice for math PhD admissions?#

The three most important parts of your application are your first rec letter, your second rec letter, and your third rec letter. Don’t sweat too much about anything else like the personal statement. And I don’t even know which schools still consider or accept the GRE after the pandemic.

-

Sometimes people advise emailing random professors. I am bit more pessimistic about this. It’s probably true that there exist professors out there who are able and excited to help mentor a research project, but I suspect they would be pretty rare (like less than one percent rare) and don’t know how I would find them. Note also that professors at prestigious schools are also flooded with emails from rando’s who think they’ve proved Goldbach’s conjecture and probably don’t want additional emails from strangers. ↩

-

Actually, this reminds me a lot of how I get tons of questions that say, “how do I get better at math”, and when I say “do more hard problems”, they feel like I’m hiding something, because I won’t tell them exactly which books to read, or which country’s problems to do, or how many minutes to study each day, or whether X goal is “possible”, etc. A lot of times I worry these study inquiries are really saying “please give me an exact list of things to do which 100% guarantee success”. And it simply doesn’t work that way. ↩

-

A lot of you have this model of an adversarial game where you and the AO are on opposite sides, and your goal is to swindle them. I don’t think this model is accurate, but if you insist on using it, I would caution you to avoid bold claims that you have a winning strategy, given that you are playing for the first time, the AO is playing for the 10000th time, the AO decides the rules, and also the AO doesn’t tell you the rules. ↩

-

Sidenote: most colleges have some introductory proof classes. I have fairly dim views of most that I have seen, but I don’t have a better suggestion. ↩

-

In fact, in my teenage years, I’m pretty sure the time I spent in high school thinking about colleges and careers — which is what all the adults told me I should be doing instead of studying math all day — was actually net harmful, and I would have been better off just playing StarCraft instead of reading about college majors. I’m admittedly a bit of an extreme case and I don’t think it ends up being net harmful for most people, but I’m trying to make a point. ↩