Rarely Asked Questions

These are questions I’ve been asked only once or twice, but which were thought-provoking enough that I want to post them anyway. This idea was taken from Paul Graham.

R-1. How did/do you have so much time?#

-

I still think energy management is more important than time management. If you are really excited about something, you will find time for it.

-

Conversely, I cut out a lot of things that weren’t important to me.

I feel high school students tend to focus too much on small changes (using Chrome productivity extensions, shaving time off X, etc.) rather than big changes (dropping entire classes or commitments). It’s not that small changes are bad, but you should consider big changes first (see so-called 80-20 rule). Aggressively dropping classes and extracurriculars that aren’t adding value to your life (e.g. not taking “advanced” classes solely for college applications) are good examples that I think people don’t do enough.

I took this to extreme measures in high school. As a senior I took a total of 2 regular high-school classes and spent on the order of 30 minutes on homework per week; as a result I had enough time to do math, write a geometry textbook, take graduate math classes, learn to play this piece, sleep 8–10 hours a day, and play StarCraft. While I don’t encourage everyone to do this, I think it illustrates my point.

For those of you who were at Math Prize for Girls in 2015, Victoria Xia made a somewhat similar point at this year’s MPFG Alumni address, which you can watch here, 49:30 – 55:30.

-

I admittedly have spent a lot of time optimizing my workflow, like typing quickly, using Vim/Linux, organizing tasks on calendars, etc. But I think that’s a secondary effect.

R-2. I’m a high-school senior who is not eligible for MOP / IMO anymore. What should I work on now?#

I guess the best advice I can give is to pick some project to work on. It doesn’t have to be (and probably shouldn’t be) something that you’re confident that you can do well in. For more on this I much like the advice suggested by Paul Graham particularly in Section “Now”.

Maybe it’s better if I gave examples of projects that I worked on (both successful and unsuccessful):

- Programming projects (GitHub)

- Installing Arch Linux and figuring out how to use it

- Writing nonfiction e.g. Napkin and EGMO (the latter was written while I was a clerk at my high school’s office)

- Writing fiction stories (which I failed miserably at; tried at least two or three times)

- K-pop dance (extremely unsuccessful)

- Creating a problem database (this took me five or six tries before it worked out)

- Creating a constructed language (failed at least five times)

Anyway, the point is to pick something that feels cool, or that you’ve always wanted to do, and then try to do it. I think this often turns out to be easier than you might expect, because you already have a lot of experience learning something that felt too hard for you (through math contests). Perhaps try to pick a project with a 50% chance of success, but really the main thing is to optimize for fun, because otherwise you won’t be able to force yourself to work on it anyway.

It’s understandably daunting to move into something in which you have little experience. But you don’t have to hard-commit to exploration projects as a full-time job, the same way you did for math contests. In other words, don’t feel locked in to any one particular thing, and don’t feel pressured to become the top N in the world: after all, the point is really for your own learning/growth/enjoyment.

R-3. What’s the most important thing that math contests taught you?#

I have a whole post on lessons I learned from math contests, but here’s one that mattered to me a lot back in high school.

In my opinion, one of the most damaging messages I got during high school is that hard work pays off. This is not true, and one of the most important life skills that math contests taught me were how to work hard even being fully aware that I might never “succeed”. Most notably, this requires enjoying the work itself rather than just as a means to an end.

In school there’s a mentality that teachers should reward “good effort”, i.e. if a student tried their best, they should get a grade of A. By extension: “if you work hard in life, you will succeed”. This turns out to be quite far from the truth. Math contests teach you this lesson much better: you can love the subject, work harder than everyone else, do everything right, and still not win the USAMO; that’s what makes it worth doing.

To quote Paul Graham:

Hard means worry: if you’re not worrying that something you’re making will come out badly, or that you won’t be able to understand something you’re studying, then it isn’t hard enough. There has to be suspense.

You don’t see faces much happier than people winning gold medals. And you know why they’re so happy? Relief.

With all that being said, I am obliged to add on that the other huge thing that contests did for me was providing me access to one of the best peer groups out there. Most of the friends that I have today came in some way or other from the math contest circuit, even though many of them will certainly not be doing math as a career.1

R-4. Would it help to have a tutor/mentor for olympiad math?#

Short answer: yes, but not in the ways people often expect. Long answer: this blog post.

R-5. Are math contests worth doing?#

The useless literal answer is “you have to decide that for yourself”. But I think the most surprising thing about math contests is the most important things you get have almost nothing to do with math (and are also largely independent of how well you end up scoring).

I think of math contests primarily as a way to stimulate intellectual curiosity, cultivate good study habits, develop independent learning ability, and build a supportive community. Despite the fact that this is nominally a competition, I am not really that interested in talent identification or differentiating students.

R-6. Should I graduate early from high school?#

There’s actually two versions of this question.

One is leaving high school a year early to do something like a gap year or other break from traditional schooling. That seems fine to me.

The second version is leaving high school a year early to attend university or start work one year ahead of time. I usually recommend against this. (And I’m not alone; I think both Po-Shen and Zuming are really against it too.)

In short, my model of high school (and college as well) is that this is the time to gain as many experience points as possible. The specifics of what domain you do this in are not important.

So to me, “my high school is not sufficiently challenging for me” seems insufficient justification to throw away a year of this growth time, because since when does high school teach you anyway? You are responsible for your own learning.

Starting college a year early doesn’t increase the amount of time you get to be an undergraduate. It just means you replace one year of high school with one extra year of being a working adult way later. Frankly, this seems like a terrible trade to me. I think many people, in practice, are going to have way more freedom to learn things on their own, or just explore interests and hobbies, while they are a student than once they become a “real adult”.

There’s no race to graduate from school; if anything, I would do the opposite and try to postpone leaving school as long as possible.

R-7. I am a parent. Give me advice!#

Here are a few great talks from the Math Prize for Girls event.

R-8. What advice would you give high schoolers?#

- Learn any difficult skill deeply. I don’t care what the specific skill is as long as it’s hard; almost anything sufficiently competitive will do. (In the process, you will learn how to learn.)

- Learn to code.

- In your spare time, build things you are totally perfectionist about. It can be a piece of software or fiction story or expository article or art project or auto-targeting kilowatt laser or whatever. But build stuff you insist on getting completely flawless. Genuine craftsmanship is deeply underrated.

- Ignore all advice that you don’t agree with, including this website. When I look back to my high school days, more than half the advice I got was bullshit. I would have been better off inverting all advice than following it.

R-9. Why do you still play video games?#

Because video games are a form of art. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

I didn’t know this growing up. When I was eleven, video games were a way to pass time during the incredibly boring mandatory vacations that my parents would drag me along. Then around when I started doing math contests, I slowly tapered off from games, finding the math problems to be more interesting.

I started playing again around when I was in college, in some cases replaying games I had completed in elementary school. Being older and allegedly more mature, the same games suddenly felt totally different from what I remembered. Because now I could see all the tender loving care that had been put into designing the game.

Every asset the art team had spent hours drawing and redrawing. Every animation that had to be programmed just right. Every soundtrack the lead composer had written after throwing away a dozen other attempts. Every little line of dialogue someone had written — especially the ones that made me grin. Every Easter egg the developers had written in. Every font that was chosen or designed from scratch. The list goes on and on, from the little things that you’d only notice if you were playing close attention, to the overall atmosphere and theme that unifies the whole work together. So many things that, now that I can see them, fill me with a sense of wonder.

Sure, the video games are fun too. But today when I play, the greatest part is being able to appreciate the experience that the developers have so carefully choreographed (and then relentlessly debugged to boot).

R-10. How can I get useful information when I ask for advice or experience from others?#

I think the two most helpful tips I have are:

- Ask for specific examples. For example, if you’re a senior choosing between colleges, and someone claims that “students at X school do cool things”, ask for examples of “cool things”. Or if someone mentions how Y experience changed their views on many things, ask for examples of what they changed their mind about.

- Ask for what was most different from what they expected. (Yes, you can actually just ask this question verbatim, it’s magical.) Paul Graham says: “you can ask [this] of even the most unobservant people, and it will extract information they didn’t even know they were recording”.

Conversely, these are also the heuristics I use when giving advice.

R-11. Any advice for writing?#

The Age of the Essay is a good starting point for context, if only to help you fix mistaken beliefs you have from English class.

After that, the two things I’d say are:

-

Write like you talk. So few people pass this basic standard it astounds me.

-

As far as practicing writing goes, I think my advice is to write about things you’ve already spent a lot of time thinking about. It’s a mistake to think that you could give me an arbitrary topic and that I would be able to write something useful about it2. I only write about things I’ve been pondering for a while (often months).

So instead of “I want to practice writing, let me think of a topic”, you should instead flip the order and say, “I have something I’ve been thinking a lot about, let me try writing out my thoughts”.

R-12. I want to write a technical textbook in an area I know well. What advice do you have?#

A few pointers:

- Write like you talk.

-

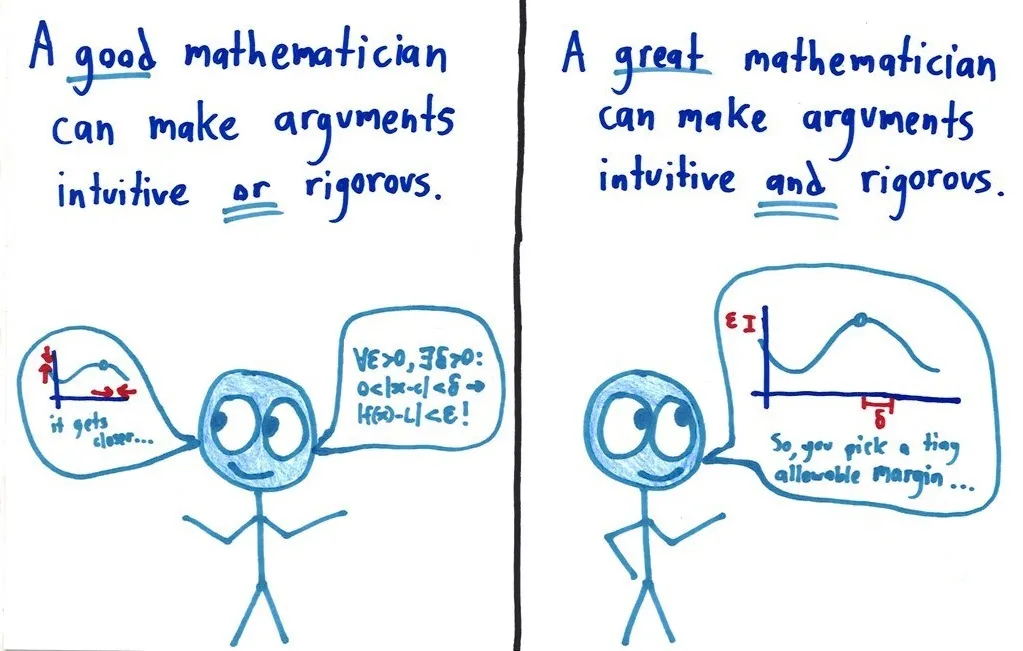

For technical subjects, write naturally. It’s not enough to be technically correct. I like the following image from Math With Bad Drawings (click to enlarge):

-

Get the proofreading and copy-editing right. If you’re not a native English speaker, get a friend or editor to help you. And get many eyes to fix errors or ambiguities. This is not something I did well for my geometry book.

-

Get the formatting right. If you’re using LaTeX, learn how to do things right. (If you’re the kind of person that uses Overleaf and

\\ \textbf{Theorem 1:}, then, well, you have a lot to learn.)

I also have a blog post on some thoughts from when I wrote my geometry book and more that might be relevant to problem-solving texts.

Kevin Zhou also has a nice passage on how good textbooks are typically written.

R-13. How do you navigate balancing doing things for prestige and enjoyment?#

Varies from person to person, but here’s a frame that helped me.

I think prestige (and money, test scores, college apps, resume-building, etc.) all fall into a bucket my former mentor describes as “seductive”. The properties are:

- They’re not intrinsically bad, and in fact can be good in moderation (e.g. getting into good colleges is nice).

- They’re impractical to avoid entirely (e.g., you can’t just ignore money).

- However, they are really, really easy to get sucked into if you’re not careful (or even if you are careful). Which is why you get to hear so many horror stories about bribing politicians, or committing fraud to impress Harvard, and so on ad nauseam.

I think this label was helpful for me because I could recognize when I was in a situation where I was like, “okay, I can’t avoid X completely, but I should be on high alert”.

It reminds me a little bit of Paul Graham’s essay on distraction, actually, particularly the quote:

If you drink too much, you can solve that problem by stopping entirely. But you can’t solve the problem of overeating by stopping eating.

-

Especially if it’s some topic IDGAF about, like an English class essay prompt. I actually generally got mediocre grades on school writing assignments, because I was not good at pretending I had something to say when I didn’t care. ↩